Some time

ago I donated 3 “to-be-done-sometime-later-to-customer’s-specifications”

Lovespoons to an auction to fund the upcoming summer mission trip for the teens

from our church. This spoon is the

first of the 3 to be commissioned and completed.

|

| Finished Spoon |

I have

wanted to do some sort of carving tutorial for some time but I lack all of the

cool video tools that many of some of my fellow bloggers have. However, this time I did, at least,

manage to remember to take pictures of most of the steps (no small task). So here is my chance to talk a bit about

this spoon and present a “video tutorial” albeit in very, very slow

motion. :-)

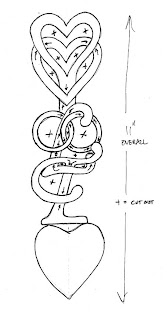

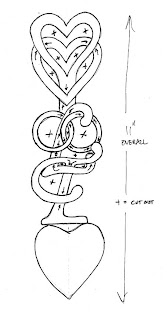

Layout and Rough Out

I have

probably belabored the design “methodology” that I use on all of the lettered

spoons way too much in previous postings so I won’t bother you with that

this time. Instead, I just give you a

play by play of the rest of the craving process. The first picture shows the paper design.

|

| Paper Layout |

You will

see that I have some small arrows on the pattern where one part of the spoon is

made to look like it is goes down and under another part of the spoon. I have found in many spoons that it is easy

to lose track of which parts go in front or behind another and the arrows make it

possible to remember. So I mark them on

the paper design and transfer them to the wood.

I start off

by simply tracing out the outline on a piece of ¾” basswood stock using a piece

of carbon paper...Oh, yeah…carbon paper. Hmmm…I’ll bet that some of you have

never used or maybe even seen carbon paper before. Typewriters are now

virtually extinct and carbon paper is one of those things rapidly fading into

obscurity right along with them. So, at

the risk of being a bit insulting, I guess I’d better say a little about what

carbon paper is and how it is used.

Carbon Paper is very thin tissue paper with a shiny, waxy form of “ink”

applied to one side. Many years ago,

B.C. (B.C. can be interpreted here as either “before computers” or “before

copiers”), if you needed multiple copies of a typed document, you would use

carbon paper to transfer the image from sheet to sheet. You would first make a “sandwich” of typing

paper separated with sheets of carbon paper and wind it into the

typewriter.

The

pressure of the keys striking the top sheet of paper would squeeze a bit of the

“ink” out of the carbon paper and deposit it on the copy immediately

below. It worked reasonably well when

you were making just a copy or two. The second copy was definitely good enough

for the files. But they got

progressively harder to read as you tried to make more and more copies. The keys would strike the paper harder on an

electric typewriter so a secretary could manage to get a few more copies but

beyond 3 copies on a manual typewriter and the whole concept sort of broke

down.

However,

vanishing typewriters aside, carbon paper is still quite valuable for

the wood carver for transferring an image from paper to the wood itself. So, my advice is: “if” and “when” you see

carbon paper for sale, you pick up a package to use now and maybe an extra

package and put it in a safe place so you have it when you need it. Carbon paper lasts forever but may not be available

forever.

OK, so let’s get that image onto the

wood…

Place the

wood on the bench, cover it with the carbon paper, “shiny side” down, and cover

it with the paper pattern. Since you really can’t see what is going on while

you are transferring the pattern, you do have to be careful that nothing

“slips” during the process or you’ll just have a smudgy mess on your

hands.

I use “push

pins” to hold everything in alignment until I’m completely done making the

transfer. I push them into the waste

stock beyond the edges of the spoon.

That way, you’ll never have to deal with the holes they leave behind

because they will all be just cut away later.

I like to use three (or more) pins because no matter where you

put them, Murphy’s Law states that one (or more) of the pins will be in your

way as you’re tracing, and you will have to move it. If you use three (or more) pins then there are always (at least) two of

them left to hold things in position while you move the offending pin. Use only two pins and I guarantee that something

is going to move and mess up the transfer.

Then, using

a pencil – a semi-sharp, handy, old Yellow #2 is always a good choice –

carefully trace the outline. If you use

a “reasonable” amount of pressure the carbon paper will leave a nice crisp

black line on the wood. Make sure that

you trace all of the lines, because once you pull the pins and remove

the paper, you can’t go back.

I hope that

it goes without saying that you orient the grain direction goes tip to tip for

maximum strength.

Then just

like probably everybody else, I use my bandsaw to cut the spoon out of the

overall piece. I guess there is nothing

much new to expound on there. Just be

careful and stay clear of that saw blade!

Cutting out the Openings

As you see,

this spoon has a lot of openings in it that had to be cleared out. I used to cut out these openings using just

my knives and chisels, but I soon learned that it was way too much like

work.:--) My current method is to cut

as many of them out with a coping saw as possible. I’m sure that a scroll saw makes this job even easier but the

finance committee at the Carvin’ Tom Workshop has never approved of such a

purchase.

As crude or

labor intensive as hand sawing may seem, I don’t really find it so. It only takes about an hour to clear all of

the openings of even the most complex spoon.

The most time consuming part of this job is loosening and re-tightening

the blade as you move from opening to opening.

I did see one of those nifty new coping saws that have “snap in”

blades recently. Someday I’m going to

buy one of them. They seem like a

really good investment. But whether you

“scroll” or “cope”, you’ll need some holes for getting the blade into the

openings.

|

| Cutout Spoon with all Holes Drilled |

At the

drill press, I carefully drill one or more holes in each of the openings. I try to use a ¼” diameter drill bit when I

can, but you can go a lot smaller than that if space is tight. If possible, you want to locate a hole near

each corner of the opening. The makes

turning around much easier. Be careful

not to put them too close to the pencil line.

You want the knife/chisel to remove that material, not the drill

bit.

You can see

my coping saw cutting board in the photo.

It is just a piece of ½” plywood with a long, tapered notch cut in the

end.

I fasten

mine to the bench top using a carriage bolt.

I splurged on one of those big, spiffy plastic thumbscrews for the

underside. That saves having to crawl under the bench to get the thread

started. They have the secondary

benefit that you can really torque them down to keep the cutting board

from dancing around while you are sawing away!

|

| Removing the Wood in the Openings |

Then, as

you can see in the photo, I just use a couple of clamps to hold the spoon to

the cutting board while I saw. Make

sure to reposition the work piece as necessary to avoid sawing into the cutting

board. And here’s what it looks like

after all the cut outs are completed.

|

| Spoon Blank after Clearing the Openings |

Carving

One of the

first things that I typically do is to carve small notches to replace the

arrows at the crossovers.

Note to self: Next time take more “in-process” photos

because this would have been a good one to include:-(.

The

position and angle of the cut help me remember what going on there. Eventually,

I work the surfaces at the “crossover” so that the curves are all as smooth as

possible. Even though there is no

actual “crossover” the eye will perceive that there is if the “joint” is nice

and smooth. You’ll “know” when you have

this right because it will magically “just look right”.

The carving

is pretty straight forward after that.

One thing to keep in mind is that in spoon carving you are you are

almost always running along the grain.

The shape and/or the direction of the grain are always changing --

sometimes very subtly -- as you meander along the length of the spoon. You will have to re-orient the spoon from

time to time to keep from “going the wrong way” with the grain. So, pay close attention. Remember, you always want to be

carving “downhill”.

So take

your time, keep your tools sharp, keep the glove on your non-carving hand and

have fun!

Carving the Bowl

Nearly

every spoon carving tutorial I’ve ever seen starts off carving the bowl first

and leaves the handle until last. I always

do it the other way: I always carve the handle first because that is the

“fun part”. And I carve the bowl last

because that is the “putzy” part. I

think the reason for this advice is to protect the newbie from disaster.

Many people

like to carve the bowl very thin.

I guess if I was going to eat with the spoon I carved, I’d like the bowl

be thin, too, so that my mouth would get more soup and less

spoon. But they call for making it so

thin that in some write-ups they talk about holding it up to the light to see

where “the thick parts” are…Yikes! that’s way too thin for me!

I guess

their logic is: “If, because you are making the bowl so thin, you punch through

before you start carving the handle then you haven’t lost much and can

just start over.” My answer to that is:

“Don’t make the bowl any thinner than about 1/8”. Since you are not sticking a decorative Lovespoon in your mouth,

it really doesn’t matter that it is a little thick. As a result, I have yet to ever punch through the bowl of

a spoon…well, no, I take that back. I did

once intentionally punch through once to add a heart-shaped hole to the

middle of the bowl.:--) After you have

a few spoons under your belt you can try that “see-though-bowl-stuff” if that

floats your boat.

There are

more ways to shape the inside of the bowl that I can even give room to

here. I have used (and do use)

several. But for someone who is

actually trying their hand at their first spoon – I assume that might be you,

because you have read this far – I would recommend a small “U” shaped

gouge.

My weapon

of choice is a gouge that is about ¼” wide and a ¼” deep. (I never could

remember which blade number goes with which blade shape). I start from the outside edge and cut

towards the middle. I make a series of

1/16” deep cuts going around and around.

After each circuit around the bowl it looks sort of like a daisy with a

couple dozen petals. You often have to

go back and clear out the center before making the next pass. When you get close to the depth you want,

make the cuts shallower and closer together.

Even as a novice you can get it pretty smooth.

Once the

inside is about where you want it, use a straight blade to work the outside to

match. As you work the shape into the

bowl, just use your thumb and forefinger like a micrometer. It is amazing how accurately you can judge

thickness. As you zero in on the magic

1/8” take it slow so that you don’t go too thin. Be very careful of the direction that you are cutting relative to

the grain. This is one place where

misjudging the cut can cause a big chunk to come out.

Sanding

I generally

start to sand with 150 grit sandpaper and drop down to 220 as it gets

smoother. If the surface is really

rough, you may need to briefly use 100 grit, but if your spoon is Basswood, I

wouldn’t go any rougher than that. It

is up to you whether you sand out the tool marks. I used to sand much more than I do now but I don’t want anyone to

forget that this spoon was carved, not molded, into shape! If you

remove all traces of the tool marks, all of the “evidence” is gone.

Take care

to vacuum, brush or wipe off the spoon whenever you switch to a finer grade of

sandpaper. If you don’t, the finer

sandpaper will drag bits of the coarse grit around leaving horrible grooves in

the surface you are working very hard to smooth out.

Finishing

My

methodology for finishing a spoon differs from most other folks. I use Sanding Sealer.

Notice:

This presupposes that this spoon is

for decorative purposes ONLY

and NOT for FOOD PREPARATION!

If you have any intension of using a carved spoon for preparing, serving

or eating food, DO NOT USE SANDING SEALER.

There are many other products

that you can get that are food-safe.

With a wood

like Basswood, sanding sealer binds the soft surface together turning it into a

“hard” surface that will take a nice shine.

Sanding

sealer comes in two types. To tell them

apart check the label. The first type,

and the one that I prefer, is what I would describe as “varnish based”. This type requires paint thinner or Mineral

Spirits for cleanup. The other is what

I would describe as “shellac-based”. It

requires alcohol for cleanup. The brands available from location to location

will probably vary, so I hesitate to make a recommendation. Both types do a fine job of bonding the

surface, but the “varnish based” type produces a harder finish and leads to a

nicer look (IMHO).

I typically

apply three coats, sanding with 220 after the first coat dries, with 320 after

the second coat and with #0000 steel wool for the last coat. Make sure you vacuum off all of the

little steel whiskers when you’re done.

Sometimes they will require some judicious “scrubbing” with a soft

toothbrush to dislodge them from some of the smaller crevasses. It just looks bad if you don’t get rid of

all of that black fuzz.

Then give the whole spoon a generous coating of a good

paste wax. Personally, I like Carnauba

wax, but I’m sure there are many other good ones. Let it “dry” for 5 minutes or so and buff with a soft rag -- old

T-shirts are great – and then hang it up or give it away!

But don’t

forget to sign it first, it might be worth big money someday:-)

One for the Bench

The only time you run out of chances is when you stop taking

them – that includes carving the bowl of your spoon really thin :-).

‘Til next time…Keep makin’ Chips!